Welp, I’ve found it guys – the DIY project I most regret undertaking: installing an irrigation system in our yard. Don’t be fooled by my friendly wave below.

Why? The short answer is that it was much more exhausting and took much longer than I expected. A professional crew could’ve knocked it out in a day or two (I know this because I watched two neighbors get theirs installed in no time while I sweated and stressed through my own installation over a three-week period). Sure, DIY projects almost always take more time and elbow grease than just writing a check – but usually, the satisfaction of doing it yourself, learning a new skill, or saving some dough makes it all worth it.

In our past ten years of DIYing tons of things, this has been the case… but while this project left me with traces of that satisfaction, it just didn’t feel like it made up for the time, stress, and pain that ended up being involved in this particular project. So I’m keeping it real with you guys and saying it like it is: ultimately I think it was the steep learning curve (this was my first big plumbing project) and large scale (our yard never felt so big) that nearly did me in.

BUT the job did finally get done, despite several hiccups (more on that later), and the silver lining is that now I know HOW an irrigation system works and I can hopefully save myself some money down the road if I ever need to troubleshoot or reconfigure the system. Well, and now our landscaping will finally have a fighting chance against the summer heat.

So I figured I’d share how I did it so anyone else who is considering the project can make an educated decision about whether they want to take it on (like if you had a smaller yard or more previous plumbing experience).

The Background

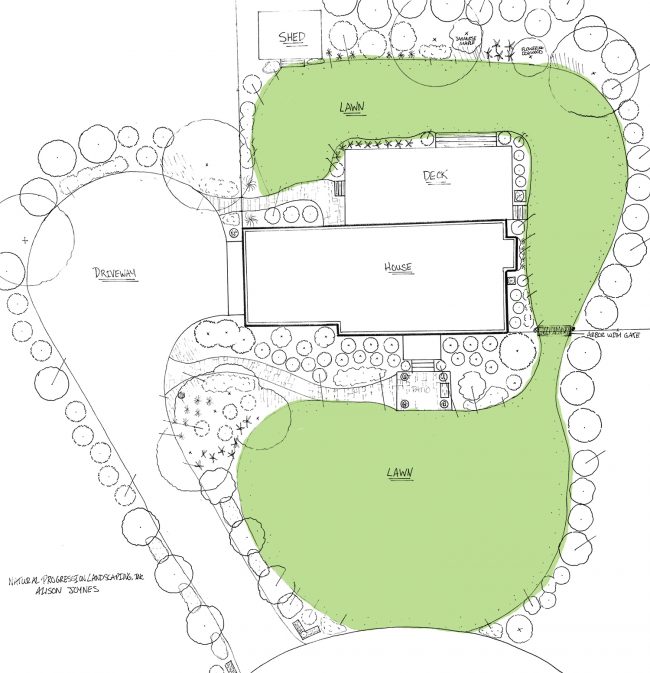

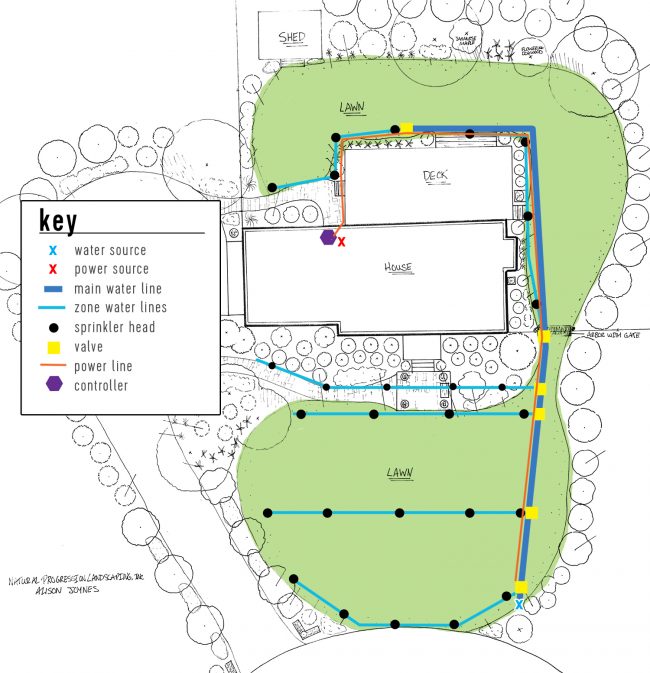

For our anniversary last year, we got ourselves a landscape plan from a landscape architect (it was around $300) because we felt like we needed a professional to set us on a course for the yard we wanted. She drew us this plan below, but she advised us not to put any money into new plants until we solved our water issue (the summer sun basically bakes everything in July and August). So I’m sharing her diagram here for reference, but we’ve made basically ZERO progress on it – and in the year since getting it, we already have a couple of things we’re thinking of changing. So our property DOES NOT LOOK LIKE THIS, but the general lawn areas are close enough – so I’m going to use this to show how the system is arranged.

So based on her recommendation, we got a few estimates from professionals to install an irrigation system. The costs were about $3,500. We were juuuust about to pull the trigger on one when a neighbor caught wind of our plan and offered to help me install my own. He had done a couple in his previous homes (his current home had one when he moved in) and said it was a pretty doable. Even may have described it as “easy.” After showing me the basics, he offered to help knock it out with me. So last September we finally got the ball rolling.

Getting A Companion Meter

The first step was going to our county’s utility office and requesting the installation of a “companion meter.” This is basically a separate water meter from the one that provides water to the rest of the house. The reason for this is that we only get charged for water on this meter, not water and sewer like our other meter. That’s because the county knows all of the water from this meter is ending up in the yard, not going back into their sewer system. Everyone we talked to said this extra step saves a lot of money over time and is definitely worth it (even the pros who quoted installations for us). The separate meter also allows us to turn it off during the winter when the irrigation system isn’t in use, without affecting the rest of our home’s water. This cost us $500 and it took a couple of weeks of waiting for it to get installed. So while we waited, my neighbor helped me plan our system.

Planning The Irrigation System Layout

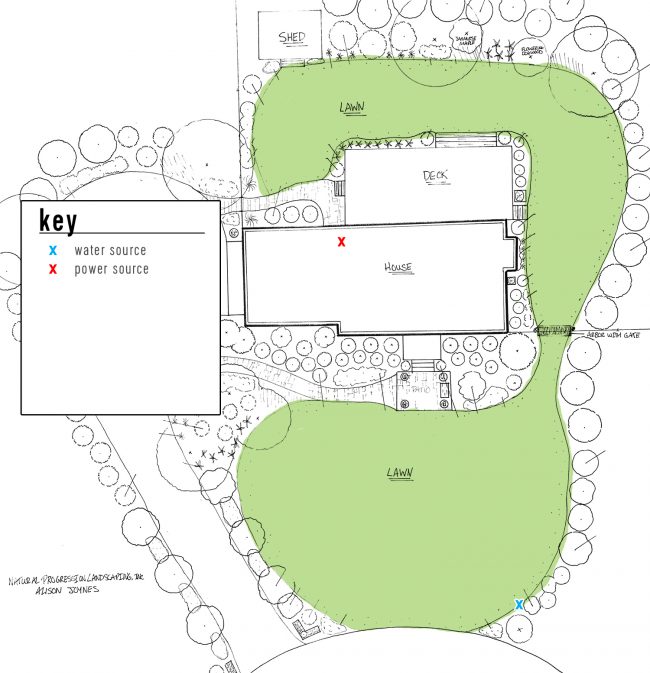

We actually picked up a couple of layout ideas from getting those prior professional estimates, but our main goal was to get water where we needed it in the least complicated route possible. For starters, you have to identify two important sources: (1) where your water is coming from and (2) where your power is coming from. The county determined the placement of the companion meter, and since we wanted to control the system from our garage, that would be our power source.

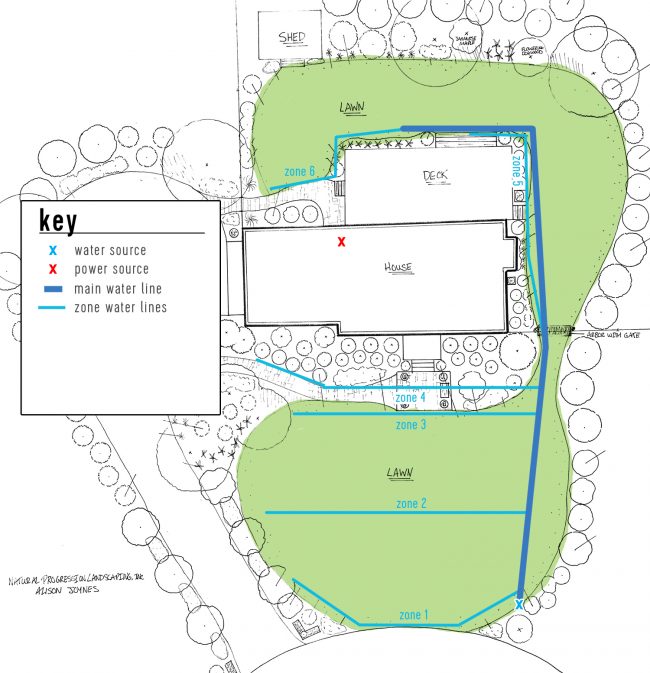

From the water source, we’d install a “main line” to supply water to each of the “zones.” These zones are basically groups of sprinkler heads that turn on or off together. The zones serve a couple of purposes. For one, depending on the size of your yard, you may not have enough water pressure to get ALL of your sprinkler heads to spray simultaneously. Creating zones also gives you more control of your watering – like if you have an area that gets drier than another, you can run just that area longer or more often (and save water/money on all the others). Each zone is fed by its own water line that branches off the main line. Ours looks a little something like this:

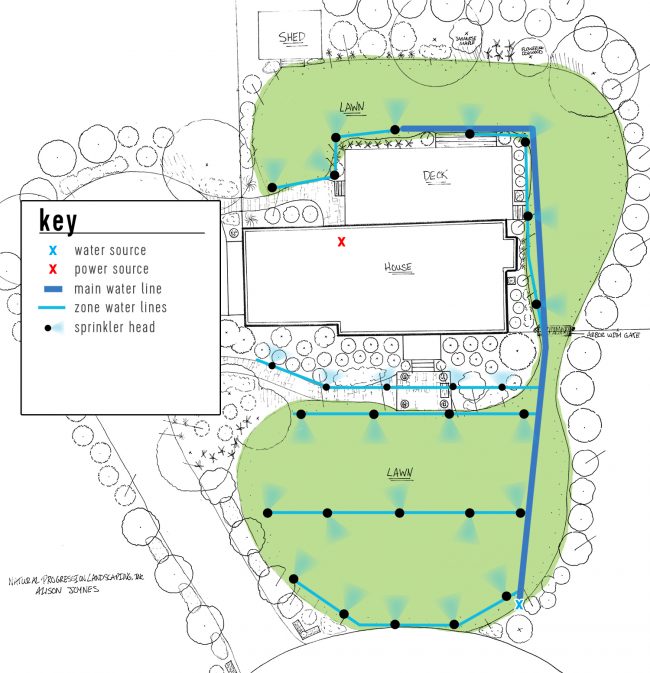

Once we had a general idea of where we’d run our water lines, we used some orange flags to mark exactly where the sprinkler heads would go. We just walked off our distances between heads (about 8-10 large steps between each one). We placed most around the perimeter of the yard, trying to limit overspray into areas that wouldn’t need watering (the woods, the driveway) or things that shouldn’t get wet unnecessarily (the deck, the house). You can adjust the arc and spray distance later to make sure you contain the water to the yard, while also creating some overlap to enough to sufficiently water the grass.

Buying Irrigation System Materials

With a general idea of the layout, I could start shopping for my materials. So let me go over what I needed (besides yards and yards of PVC pipe and a smorgasbord of PVC fittings and connectors). First up, the sprinkler heads. I went with these Hunter Rotor heads at my neighbor’s recommendation for most of the yard, and some smaller mister heads from Lowe’s for our front mulch bed. In both cases, most of it is buried underground and sits just barely above the dirt line. When the water turns on, the pressure pops it up (as shown below) and rotates back-and-forth in whatever arc you determine, or in a full 360 degree function.

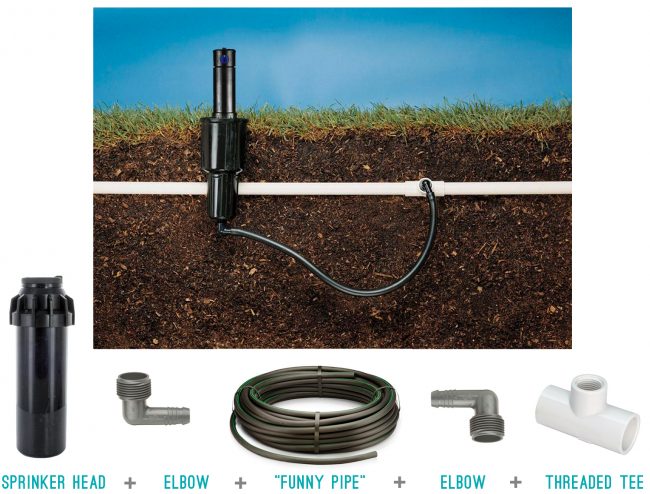

Each head attaches to the PVC water line via some flexible swing pipe (also called “funny pipe”) and some swing pipe elbows on either end (one screws into the bottom of the sprinkler head, the other into a threaded tee installed in your line). I’ll show you how this works later, but know that for each sprinkler head, you’ll need these as well.

Each zone is controlled by a valve. It’s a little electronic device that is installed at the start of each of your zone water lines, and controls when water flows into that zone. So you need one valve per zone, along with a valve box for each one. Since the valves live underground, the box keeps dirt off the valve and gives you access to it without having to dig.

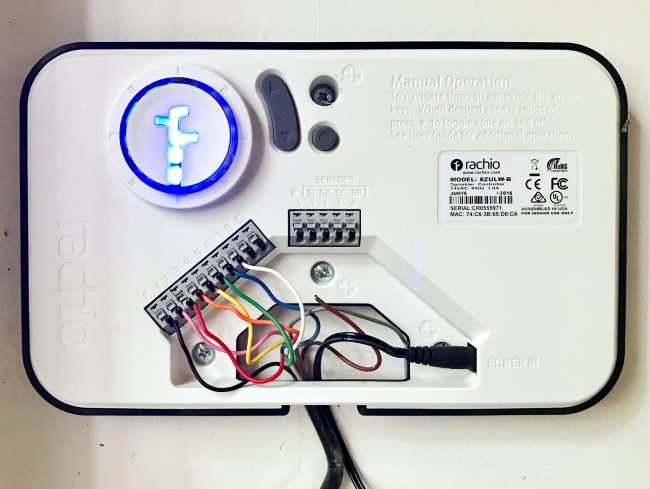

The valves are controlled by a controller, which is where you’ll program your watering schedule (aka: when each zone turns on, and for how long). We chose this “smart” Racchio sprinkler controller and we LOVE it. All the programming is done via an app on your phone (or even your Alexa!), so it’s much easier than deciphering knobs or buttons on the actual box. Plus, it connects to a local weather station so it will skip a scheduled watering when it knows it has recently rained OR if rain is in the forecast (meaning you don’t have to buy and wire your own personal rain gauge – it’s so smart and has already saved us a ton of water on days we don’t need it).

You also can opt in to get a text or an email notification when a scheduled watering starts, stops, or is skipped. It’s a bit more expensive than a basic controller, but it’s been WELL WORTH IT. Just make sure you buy a version with enough zones for your yard (we have 6 zones, so I bought the 8 zone version – which gives us room to grow if we ever need to add more).

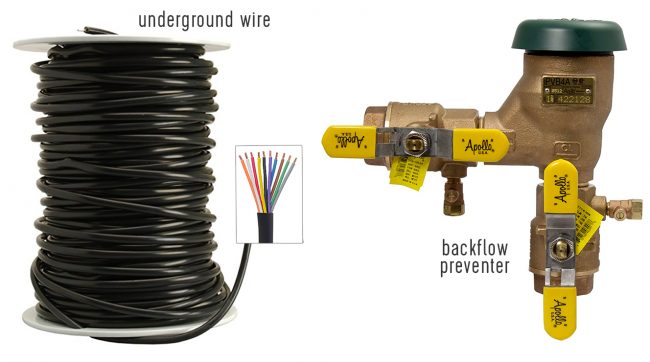

The controller plugs in near your power source (again, ours is in the garage) and is wired underground to each of the valves. So you’ll need some underground wire with enough strands so each zone has it’s own dedicated line (we got this 10-conductor version, since 10 strands were plenty for our 6 zones). It’s fine if it’s got extra, you just don’t want too few. The last item on the list is a backflow preventer, which is a device our county requires you to install to prevent water in your system from flowing back into the water main. It’s one of the few above-ground parts of an irrigation system, so you may have noticed them in yards with a sprinkler system.

Digging Your Trenches

The first step in installing your system is digging trenches for your pipes to run. CALL 811 BEFORE YOU DIG ANYTHING. They will come mark your property for utility lines so you don’t damage anything or hurt yourself. As we detailed in our podcast (Episode #21) our local utility failed to mark a gas line that we knew ran along our yard, so I ended up having to dig a large section by hand so that I could be extra vigilant for any utility lines. A neighborhood kid happened to be testing his new drone when I was doing this, so I have overhead evidence of some of my work!

For the rest of the yard, I rented a trencher from our local Home Depot (it was $88/day). I also had to rent their truck to get it home, since it wouldn’t fit in my car. So I used that as a chance to also buy loads and loads of PVC pipe (both 1″ and 3/4″ widths).

The trencher was VERY heavy and it took me and two other guys to get it in and out of the truck. Even once it was down, it was quite a beast to maneuver. You basically pull it backward steadily and the “blade,” which you can set to plunge into the earth at various depths, churns the dirt up, and leaves a narrow trench. The trencher is a bit tedious/slow to use and it still proved to be pretty exhausting, between yanking its weight and the vibration of you felt through your bones the whole time.

In fact, my neighbor (who I’ll be the first to admit is much stronger than me) ended up doing most of the trenching because he had better control over it than I did. Can I blame all my shovel digging earlier in the day for not being up to the task? While he did that, I wasn’t off the hook though. I shoveled the trench alongside our front walkway (as not to damage it with the machine) and I worked on running a pipe under the sidewalk itself (for the “mulch bed zone”). I did this by ramming a PVC piece through the dirt with a sledgehammer.

Digging – including renting & returning the trencher – ended up consuming most of the first day, which was a surprise to all of us. My neighbor thinks last time he did this he rented a smaller cable installer which digs a 4″ deep trench. I can’t speak to whether that would’ve worked or not, but it might be worth asking at your tool rental place – since it does appear to be easier and faster to maneuver.

Laying Your Irrigation System Pipes

Once your channels are all dug, it’s really just about connecting everything together. This is a straightforward process, but – depending on the size of your system – can be tedious and time-consuming. I started by loosely laying out my PVC along my trenches. I used 1″ for my main water line and for the first 2 or 3 sprinkler heads on each zone line, at which point I reduced it 3/4″. This was just a cost savings suggestion from my neighbor since 3/4″ is slightly cheaper.

To connect all of the pipes together, you use various couplings and elbows that get cemented in place. The process looks a little something like this. Start with this primer, like this purple guy.

Using the built-in brush, coat the ends of the PVC pieces you’ll be connecting, making sure to go all the way around – it’s very thin, so try not to drip on anything like sidewalks or driveways. Your pipe should be clean and dry too.

The primer dries within a couple of seconds, at which point you can apply your cement. We used this blue kind.

Same deal: use the brush to coat all sides with it. It’s pretty gooey, but again try not to drip it on anything you don’t want a blue stain on.

Repeat this process on the other surface you’ll be attaching it to – in this case, the inside of a coupling I had already cemented to the other pipe.

Then you push the pieces together, giving it a slight twist and holding for about 30 seconds. I usually do this with two hands to apply pressure from both sides, but one hand was occupied with a camera phone for this pic.

If ever I needed to cut a piece of PVC, I used this ratcheting pipe cutter. It’s super easy to use, so well worth the $25 price tag.

I know this doesn’t seem like a difficult task, and it’s not. But I had LOTS of connections to create and working hunched over (dare I say “in the trenches”?) and repeatedly pushing pipes together with some force slowly took a toll on my back and shoulders. I had some of the worst sleeps of my life during this project because I had tweaked my shoulder in a way that didn’t allow me to lay on it. #sidesleeperproblems

Installing Your Valves

Again, the valves are the devices that need to be placed at the start of each zone because they control when water is allowed through to that zone. To install into your piping, the valves I used took some threaded couplings that I tightly secured with some plumbers tape and a couple of tightening twists of my wrench.

I don’t have any picture of the installation, but I used the same cementing process to attach the couplings to the rest of my pipe, right where each of my zone water lines branched off the main line. Just be sure to install it facing the right direction (mine had arrows to indicate the direction of water flow) and don’t forget to put a valve box around them too. Mine had to be added during the pipe install, but some can lay over your pipe afterward.

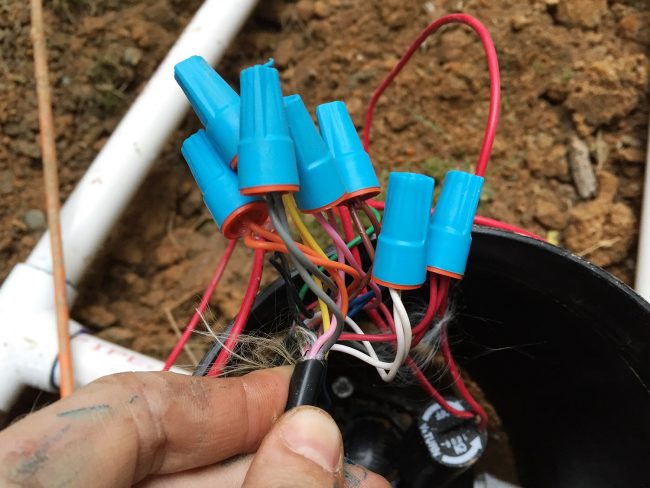

The valves need to be wired to your controller, so I’ll show you this part now, but I actually did my wiring after all of my piping was completed. Again, I’m using a 10-conductor underground wire that, when cut open, has 10 strands of different colors.

I first installed one cut end into my Racchio controller. I made black the common wire and then just went in “rainbow order” to help me keep my zones straight. The gray and brown wires could be used later if I wanted to add two more zones. And long story short, the zone 2 wire (red) jammed as I tried to put it in, so it didn’t connect fully…. buuuuut I can’t get it lose. Rather than buy a replacement controller, I just bypassed Zone #2. That means I’m using Zone #1, then Zones #3-7 to control my six zones. One of the many small annoyances of this project, but at the end of the day, no biggie.

With my controller wired (but still not plugged in) I then threaded the wire across the yard, through my main line trench, all the way to my first valve. I left excess as I went, since it was better to have extra than not enough.

At each valve, I had to connect one of the vavle’s red wires to the black (common) wire and the other to the color that would control that zone (this would be my Zone #5, so I used green to correspond with the wiring at the controller). This would literally be the end of the line for the green wire, since it’s not needed on the valves further down the line.

But in order to continue all of the other colors down the system, I wired them one-by-one (using waterproof wirecaps) to the same color strand on my next section of wire. Same goes for the black common wire, which is why you see two black strands going into the wirecap pictured above. In retrospect, I probably could’ve figured out a way to not cut all of the colors at each valve and just extract the colors needed – which would’ve saved lots of time. Maybe next time (ha! NEVER!).

By the last valve the only strands left were the Zone #1 color (pink), the common (black), and my two unused colors (gray and brown). I continued my unused colors throughout the thing so that I could add a new zone at any point within the system without having to rebury a whole new line.

Installing Your Backflow Preventer

This is probably where I encountered the most hiccups, so forgive my lack of photographs (I tend to slack on documenting when things aren’t going my way). This diagram shows pretty much what I was aiming for, based on what I had seen on other houses in the area.

The only thing not shown is also a blowout, which is a pipe that sticks out from the main line that remains capped all year, until the fall when you need to winterize your system (aka, get all the water out of the lines so they don’t freeze and bust things up). To do this you attach an air compressor to the blowout and literally blow water out of the pipes through the sprinkler heads.

So here’s what mine looked like at one point – sorry my only pic is from when I had taped off the backflow device in order to spray the exposed PVC brown to blend in with its natural surroundings. You can see my blowout there on the bottom right. Spoiler alert: there are some mistakes here, but I’ll get there in a minute.

Actually, my first “saga” with the backflow installation was literally getting the darn thing connected to the county water line. Their pipe was copper, so I had to buy a special SharkBite coupling that would connect copper to PVC. The connection was about 2.5 feet in the ground, which made it EXTREMELY difficult to work on – and after a couple attempts, I just couldn’t get the lines to connect without leaking. We eventually called a plumber, and even his first guy couldn’t get it to work either. The next guy finally got it, and determined there was a gash on the underside of the county’s pipe (which none of us could see) and it wasn’t until he cut that part of the copper pipe off did we get a leak-free connection. It was super annoying and cost us about $150 to resolve.

So all seemed good in the backflow preventer department from there on out. But fast-forward to this spring when I finally get my system inspected (you can hear why it took that long in podcast Episode #49) and I find out THE REQUIREMENTS HAVE CHANGED and my install is now incorrect. In fact, I fail the inspection in three different spectacular ways. So I have to dig it back out again. Which, as you can imagine, I was REALLY excited about.

Here were my three errors (which previously had been permitted since our neighbor has his system configured this way):

- I hadn’t installed a main shut-off valve before my backflow device (I thought the county shut-off was sufficient, but apparently not)

- I hadn’t installed couplings on either side of the device, which can be unscrewed for winter storage of the backflow preventer

- I had put my blowout before the backflow preventer when instead it should go after so you’re not blowing pressurized air through the backflow

Again, what I did matched how others looked along my street (and even what is still shown in some of our county’s documentation) but it wasn’t gonna pass anymore. Times had changed. I had changed. My opinions of DIYing an irrigation system had definitely changed.

It took me a couple of hours to reconfigure everything and now it looks a little something like this.

So I’m certainly not the authority on backflow preventer installation (and it likely varies from county to county), but now you know at least as much as I do.

Installing Your Sprinkler Heads

With my valves and backflow preventer installed, I moved on to installing my sprinkler heads. Previously, as I had laid my zoned water lines, I had incorporated one of these set-ups whenever I came upon one of my orange flags.

This follows this schematic that I showed earlier (and again below). To create a spot in my line for a sprinkler head, I incorporated a threaded tee connection into my line. This is basically the same as a straight coupling but with a third hole on the top where I could twist in a threaded swing pipe elbow.

I assembled these connections in bulk one night on the couch – twisting the swing pipe elbows into a couple dozen tees, as well into some white elbows that would go at the end of each zone’s water line. They were pretty easy to thread by hand, but then I stuck a screwdriver in the end of the gray elbow to give me leverage to tighten them a couple more turns. I also cut small (18″-ish) sections of funny pipe in bulk and attached them. They just twisted on with a bit of pressure.

That same night on the couch I also one prepared my sprinkler heads in bulk (I had 27 in total, including misters). This meant twisting the small gray elbows into the back of each one…

…and installing red nozzles into each one based on the type of spray I wanted. This took longer than you’d expect, since I had to use that special white “key” to pull the sprinkler head out of its chamber to access the nozzle hole. It took a surprising amount of force to keep it from snapping back in (note my white-fingertip grip).

The next day I was able to install all of my sprinkler heads to the other end of the funny pipe, cutting it to the desired length so that I could position my sprinkler head exactly where I wanted it in the ground.

I hand dug holes for the pipe and sprinkler heads to be buried, so that just the very top of the each spinkler head would be exposed. You want it low enough that you won’t catch your mower blade on them.

Then it was time to go to each head and set the spray arc. I won’t get into the detail of this (just follow your manufacturer’s instructions) but it did involve some more yanking with that special key tool, so I’m not going to say it was fast and easy (I’d best describe it as tedious, especially since we have 27 sprinkler heads!). Oh and it’s helpful to do it with the system running so you can watch exactly what your water hits and make adjustments as you go.

Finishing Touches

The last few steps were, for one, filling in all the holes and trenches that had crisscrossed our yard for three weeks. Thanks to some heavy rains in there at some point, my dirt piles had turned into dried, muddy clumps so it took a bit of effort to get everything filled in, but we eventually got it done.

It was mid-October by this point, so I was running short on time to regrow grass on those dirt spots, so I tossed down some grass seed and let the new irrigation system do its thing.

We’ll still need to overseed this fall, but that last-ditch-effort seeds last fall actually did a pretty good job considering their late start. Phew! I’ll take all the good news I can get!

Conclusion

At the end of the day, I do feel accomplished for having completed this project. But between the barrage of hiccups, the tedious physical exertion, and the general stress I put myself under during this task – it will go down in history as the DIY project I most regret not hiring out (and I probably wouldn’t recommend to anyone unless they have a smaller yard or more previous plumbing/irrigation experience). Not counting my backflow prevention revision this spring, it took me about a month from planning to completion. That’s not working non-stop on it for that time period, of course, but still much longer than the 2 or 3 days my neighbor had originally predicted. And I don’t blame him for “getting me into this mess” by any means. He couldn’t have anticipated some of the challenges (the slow-to-use trencher, the copper pipe connection, the changes to the inspection requirements, etc) and I’m very grateful for his help that first weekend.

The silver lining is that I went back through our receipts and it looks like our grand total was around the $1,800 mark, so we did save about $1,700 versus the professional estimates. And that doesn’t include the fact that I now know how to winterize it in the late fall and how to get it ready each spring (something that people often pay $75-$150 a year to have an irrigation company do). It also stands to reason that since I know how the system works, I should theoretically be able to repair things or add onto it should I ever need to. So yes, that money saved is satisfying, and these skills will definitely come in handy over the years of maintaining it and draining it and all that stuff. But yeah, not the smoothest project I’ve ever done. Perhaps I should dip into that savings for a massage to try to work out that persistent shoulder kink…

*This post contains affiliate links